Written by Hamid Dabashi

Eyes must be washed,

In a different manner must we learn to see

—Sohrab Sepehri

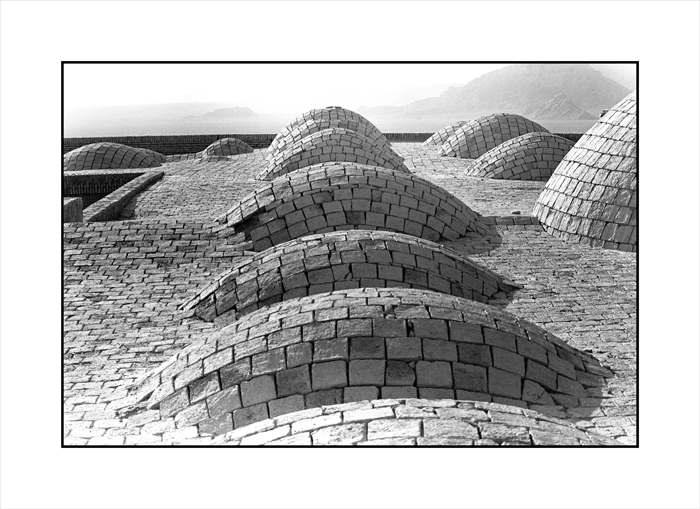

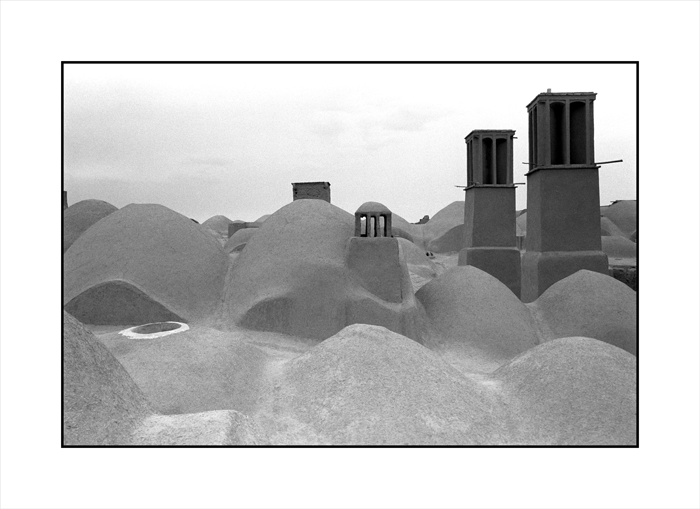

The posthumous awarding of the Spectrum International Prize for Photography of Lower Saxony (VII) to the preeminent Iranian photographer Bahman Jalali (1944-2010) is a unique opportunity to reflect on the lifetime achievement of an artist who for half a century was the vision and vista of his people. Just a few months before his untimely death on 15 January 2010, Iranians were yet again marching in their masses of millions to reclaim their public space in yet another manifestation of their democratic aspirations. Jalali was destined to have kept his people company through the thick and thin of their relentless quest for liberty—showing them where they were, what they were doing, both the sad and the soaring moments of their failures and success. Master Bahman Jalali was stoic in his photographic demeanor. As his desert photography clearly shows, he had a patience and poise that was rooted in the subterranean memories of time immemorial. From the desert architectures of his homeland to the uproarious revolutionary uprising of his people's most repressed desires, Bahman Jalali had a calling to capture the illusions, the mirage, that make the realities of their humanity possible, plausible, and trustworthy.

The Fundació Antoni Tàpies in Fall 2007 and the Sprengel Museum Hannover in the summer of 2011 were the successive sites of two major exhibitions that celebrated an Iranian artist who over a lifetime had trained generations of photographers who are now extending his testimonial vision and photographic wisdom into posterity. Though the world of photography lost a magnificent artist very early and at the zenith of his creativity, Bahman Jalali continues to live not just in his timeless work but also in the agitated soul of the lenses he has bequeathed to and taught his students how to turn. His heritage extends, however, far beyond his immediate and distant students. He has planted his lens in the mind's eyes of his people. Ostad Jalali (Master Jalali), as they call him affectionately in Iran, was a visionary artist that in this panoramic full view is now the visual register of a world he was destined to document, an artist who over the span of a lifetime polished the active intellect of his lenses so perfectly that he became the photographic soul of his people. If the two series on

Revolution and

War are capturing the choreography of the trials and tribulations of a people, the series that Bahman Jalali called

Image of Imagination reflects the more meditative spaces that Ostad Jalali was discovering in the uncharted territories of his photographic soul. There and then he has captured the evasive illusions without which realities have no way of suspending their commanding presence.

The Making of A Visual Modernity

"Towards the end of the reign of that pious King and Fighter for the Faith, Muhammad Shah [reigned, 1834-1848], may The Almighty clothe him in light," thus says I'temad al-Saltaneh, a historian of the Qajar dynasty (1789-1926), "Monsieur Richard Khan who at present teaches English and other languages at the Dar al-Fonun used, with much toil, to take pictures on silver plate. In the early part of the reign of our present Shah [Nasir al-Din Shah (reigned, 1848-1896)], may our souls be sacrificed for him, when the Dar al-Fonun [a modern college] was built, Monsieur Krziz the Austrian artillery instructor, made some photographic experiments on paper." This passage is the earliest narrative record of how the art and science of photography found its way into Iran—an account that is deeply rooted in the history of modern Iran in the colonial context of its emergence as a modern nation-state.

Rooted in that beginning and in its enduring context, Bahman Jalali's prolonged mediation between the art of photography and the cultural condition of modernity in his homeland has now produced the massive evidence of a lifework with his indelible signature written on its visual vocabulary. Not only in his own massive production over more than thirty years but in fact in his sustained endeavors as a collector, curator, historian, and a repository of transmission to the new generation, Bahman Jalali has been at the forefront of a national photographic project that visually informs his people's encounter with colonial modernity. His work and activities are thus the indices of the enduring role of photography in the emergence of his country as a modern nation-sate over the last two hundred years. Bahman Jalali's work, as a result, at once complicates our understanding of Iranian encounter with colonial modernity and maps out the various visual regimes that have been constitutional to the formation of Iranian modernity. Evident in his work and running through the silhouettes of his photographic memory are the active registers of a

visual modernity coterminous with a national narrative at the roots of Iranian collective consciousness.

The origin of photography in mid-nineteenth century Qajar encounter with European colonialism notwithstanding, the more immediate signs of Bahman Jalali's

visual modernity is in fact rooted in the rise of Persian

literary modernity into which his generation of artists were born and upon which it was nourished. The nature and disposition of that visual modernity is not merely historical but far more effectively archeological. Bahman Jalali's generation of photographers is as much informed by the history of photography in Iran as by the emotive universe—visual, literary, poetic, performative—into which they were born. Less than a decade before Bahman Jalali was born in 1944, and precisely in the same year that Pablo Picasso was deeply disturbed by the rule of fascism in his homeland and furiously at work on his

Guernica in Paris, a European educated Iranian writer named Sadeq Hedayat (1903-1951) traveled from Iran to Bombay (Mumbai) ostensibly to help with the Persian dialogue of the first Iranian films that were being made in India, but in fact to learn the middle Iranian language of Pahlavi—and then most famously ended up publishing a limited edition of a handwritten copy of a short novella that was destined to change the course of Iranian

literary modernity. The reign of general Franco in Spain (1936-1975) was no less dictatorial than the monarchy of Reza Shah (1926-1941) and his son Mohammad Reza Shah (1941-1979) in Iran—and yet from the heart of Reza Shah's tyrannical darkness emerged the rays of literary and artistic hope for a life otherwise than evident. The publication of Sadeq Hedayat's masterpiece,

The Blind Owl (1937), marks the zenith of Persian literary modernism. Although the origin of Persian literary modernity goes back to mid-nineteenth century (as early if not earlier than the origin of photography), it was not until Sadeq Hedayat gave it a robust imaginative surge that it became a major force in Iranian cultural modernity.2 In the creative character of Sadeq Hedayat and the literary modernity that he initiated and marked we might thus locate the immediate cultural condition into which Bahman Jalali was born and was then cultivated as a photographer of uncommon versatility and insight.

The fact that Sadeq Hedayat had written

The Blind Owl while deeply influenced by such European writers and poets as Frantz Kafka and Rainer Maria Rilke, whom he read in French, but published it while in India and studying Pahlavi, in and of itself, points to the cosmopolitan transnationalism of the culture that had preceded him by more than a century and that had now come to full creative fruition.

The Blind Owl gradually emerged as the defining moment of Iranian literary modernity—a masterpiece that to this day remains unrivalled and unsurpassed; while making its author—a disaffected member of the Qajar aristocracy who renounced his ancestral privileges and opted for a short literary life that ended with his suicide in Paris in 1951—the most prominent literary modernist of his generation. No learned and cultivated Iranian of Bahman Jalali's generation, born after the publication of Sadeq Hedayat's literary masterpieces, was immune to his enduring influence and as such was markedly different from his or her parental generation in literary and cultural sensibilities. One might in fact divide the modern cultural history of Iran into pre- and post-Sadeq Hedayat periods, when the literary—and by extension visual, poetic, and performing—vocabulary of an entire nation of sentiments changed for good.

When we look at Sadeq Hedayat's literary output today, we see a relentless and probing soul navigating a whole spectrum of creative and critical writing that ranges from novella and short stories, to studies in linguistics, literary criticism, folklore, literary translation, and drama. Among his other works, Sadeq Hedayat prepared a critical edition of Omar Khayyam's quatrains, wrote some of the most enduring examples of modern Persian drama, a number of travelogues, exquisite and biting satire, short stories that constitute the cornerstone of Persian literary modernity, treatise on vegetarianism, translation of literary sources from French and ancient texts from Pahlavi. In his short but exceedingly fruitful life, Hedayat set the record for a

literary modernity and creative cosmopolitanism that have been definitive to Iranian cultural modernity for over two centuries.

Invoking the memory of Sadeq Hedayat and the zenith of Persian literary modernity and creative cosmopolitanism that he best represented is one among any number of other hallmarks of modern Iranian cultural history one can choose to mark the right angle when today we approach, look at, and begin to converse with the extraordinary lifework of Bahman Jalali's photographs collected at Tapiès Fondation in Barcelona. One might equally point to the groundbreaking work of Nima Yushij (1896-1960), the founding father of modernist Persian poetry, or before him to Fath Ali Akhondzadeh (1812–1878), a pioneering figure in critical thinking about literary modernity, or after him to Mirza Aqa Khan Kermani (1853-1896), perhaps the most gifted cultural modernist of the nineteenth century. In visual, performing, literary, poetic, and critical modernism, Bahman Jalali has a genealogy of creative characters behind him that span over the last two hundred years of modern Iranian history. Bahman Jalali's generation of visual artists carry in the constellation of their caring and critical lenses (in the poetics of their visual memory) that creative cosmopolitan that for over two hundred years has been the hallmark of Iranian cultural modernity—an anticolonial modernity that was the precise antithesis of European colonial incursions that was the defining trauma of much of the colonized world.3

Born in 1944 and active for almost half a century, Bahman Jalali is one of a handful of artists who is chiefly responsible for having brought the art of photography to full artistic recognition and social prominence in Iran—beginning with the rise of the Pahlavi monarchy (1926-1979) to political prominence and continuing in the aftermath of an Islamic revolution (1979-present). The art of photography that Bahman Jalali now best represents came to full cultural prominence in the 1960's, with such globally celebrated artists as Reza Deghati, "Abbas," the late Kaveh Golestan (1950-2003)—tragically killed while documenting the US-led invasion of Iraq—and later sublated in the artistic works of such other prominent artists as Amir Naderi, Abbas Kiarostami, and Shirin Neshat. Although the origin of the art of photography in Iran goes back to the beginning of photography itself, with European colonial photographers among the first to have taken the very first photographs of Iranian landscapes and peoples, as an art form, photography began to enter the domain of Iranian

visual modernity early in the twentieth century with the work of such legendary photographers as Antoin Sevruguin (d. 1933).5

As a photographer, Bahman Jalali's art is deeply rooted in that history and tradition, while his attraction and fascination with photography is embedded in a generation of Iranian artists, intelligentsia, and literati that cultivated its interests far more in the wide domain of social practices than in the specific domain of scholastic learning. Having never "studied" photography in any formal schooling, Bahman Jalali has taught it in a number of Iranian universities. The range of his accomplishments as a photographer has been much celebrated in his own homeland. He is a founding member of Iranian photography museum, and been on the editorial board of the leading photography journal in Iran. As evidenced in this compressive collection of his work collected at Tapiès Fondation, Bahman Jalali has photographed the four corners of his homeland, documented its wars and revolutions, pictured its desert landscape, recorded the facial topography of his people, and lived with fishermen, nomads, peasants, and city dwellers alike, while widely familiar with the vacated quietude of Iranian cities and villages. Looking at Bahman Jalali's photographs is to witness the evident and hidden history of his people—from the streets and battlefronts of its revolutions and wars, to the vacated landscape of its deserts and small towns, and then down to the distant corners of its photographic memories. Bahman Jalali's artwork is the living memory of a visual modernity that is constitutional to his nation's historical passage to moral and normative agency.

The Art of the Impossible

The art of photography that Bahman Jalali best represents had an inconspicuous beginning in his homeland, but it had to witness and envision much before it cultivated a creative soul at the focal fusion of its caring and curious camera. When one of the most prominent philosophers of the nineteenth century Iran, Molla Hadi Sabzevari (1797-1873), saw a picture of his taken by the court photographer he was absolutely flabbergasted and considered it a bizarre miracle, for in his considered philosophical opinion "only the human spirit . . . was capable of imprinting and recording images, and this faculty was beyond the scope of any man-made machine." It would be a long and tumultuous time before that creative soul were to be detected and invested in the camera that today Bahman Jalali holds in his hands and takes picture of his homeland and its peoples. From the time of Molla Hadi Sabzevari forward the history of photography and subsequently cinema is predicated on a rich and diversified tradition of paintings as manuscript illustration and the so-called "coffee house painting," in which visual rendition of narrative stories have given glimpses of a far more richer and diversified visual sets of imageries dominant in Persian literary and performing arts. In such masterpieces of Persian poetry as Ferdowsi's (940-1020)

Shahnameh or Nezami's (1141-1209)

Khamseh, we read very vivid visualization of the most dramatic (heroic or erotic) aspects of the stories. The subsequent manuscript illustrations of these poems, the so-called "Persian miniatures," are imaginative renditions that mark the most immediate manner of visualizing those stories. When the art of photography and subsequently filmmaking arrived in Iran, from mid- to late-nineteenth century forward, those rich and diversified literary and poetic traditions were very much alive and on the mind of Iranian photographers and filmmakers.

Beyond its origins in Persian literary, poetic, and performing arts, the art of photography now evident in Bahman Jalali's lifework was the forerunner of contemporary Iranian cinema. Such prominent Iranian filmmakers as Amir Naderi began their career as photographers, while others like Abbas Kiarostami have turned to photography after a very successful cinematic career, while still others like Shirin Neshat have mixed and matched photography and filmmaking in the art of video installations. The confidence of generations of Iranian filmmakers, from Forough Farrokhzad, through Amir Naderi, and down to Abbas Kiarostami are invested in the moment that Bahman Jalali picks up his camera and looks through it at a soldier with his gun hanging from his back, sitting in his trench, his back to Bahman Jalali's camera, and looking through his binoculars at the vast anonymity of a deserted landscape. How close to that soldier do you get, how far, how much do you close or open your frame, what lens you use, what time of the day it has to be, and above all where do you stand to hold your camera in your hand without disturbing the peace of that warring posture—all these and myriads of other imperceptible questions are always already asked and answered before the camera of a photographer like Bahman Jalali becomes the hidden conscience of an entire people, a whole nation of sentiments and ideas—read and recorded for the whole world to see. When Molla Hadi Sabzevari saw his own picture, he thought it the product of a soulless machine. It would be quite some time before that machine was indeed invested with a creative soul that caringly captured the trials and tribulations of a people.

Remember the photograph of Kim Phuc, the totally naked nine-year old Vietnamese girl from the village of Trang Bang taken on 8 June 1972 by Nick Ut as she and a number of other brutalized villagers were running down a road, screaming in pain from third-degree burns suffered during a napalm attack on her village in Vietnam. War photography was never the same after that picture by Nick Ut. By virtue of this picture of Kim Phuc, war photography can be divided between a pre-Nick Ut and a post-Nick Ut period. Bahman Jalali's generation of Iranian photographers of war and mayhem—which includes such world renown figures as Reza Deghati, "Abbas," and the late Kaveh Golestan—are the product of the post-Nick Ut war photography: The urgency, terror, brutalized humanity, and unsurpassed savagery of warmongers all dwelling and dreaming in their defiant and yet frightened consciousness. In his war and revolution photography, Bahman Jalali has the Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut and by extension the legendary Hungarian photographer Robert Capa (Andrei Friedmann, 1913-1954) guiding his camera in his mind.

Once upon a time the camera may indeed have been a machine without a soul. Much carnage and despair has happened in the ravaged soul of humanity for the camera now to possess (and to be possessed by) a creative soul.

The Totality of the Lifework

Chapter and verse, the extraordinary collection of Bahman Jalali's lifework (from the heart of Iranian desert architectures to the hidden horrors of its revolutions, from the archival corners of its antiquarian studios to the full scale uproars of its wars) over the last almost half a century is the visual evidence of a cosmopolitan culture that extends from visual to literary to performing arts. The challenge that a contemporary audience alien to that cosmopolitan culture faces when looking at Bahman Jalali's artwork is how to reach for the visual vocabulary and the emotive universe of that worldly culture, passing the hurdle of the alienating effect of its aggressive anthropologization in a post-9/11 world that must re-learn how to look at a work of art and practice an aesthetic exegesis that allows the work itself exude its hermeneutic resonances, its cultural artifacts, social conditioning, political practices. What is perhaps most important in Bahman Jalali's collected work is the signature authority of a lifetime of committed artistry that ipso facto disallows whimsical appropriation into one direction or another—in either overtly anthropological or merely political terms. Here stands before its audience a massive body of evidence documenting the totality of an artist's lifework, awaiting a narrative appreciation.

The totality of Bahman Jalali's lifework informs its specific items. Take any of the pictures of his exhibited work you wish. Here is an emptied and vacated alley in the city of Bushehr. The iconic registers—or the denoted and connoted messages of the picture, as Roland Barthes would say—of the picture are yet to be globally conjugated, trans-regionally tabulated, and visually read. The picture is loaded with its emptied sensibilities. An abiding anonymity at once informs and depletes the picture—if it were to be seen in exclusively its own terms. What makes this picture move in order to begin to punctuate an emotive universe is if we were to watch it adjacent to another picture in the same series, yet another emptied street, and then move on to another, and then another, and so on. Thus viewed, every picture becomes a commentary (a visual caption, one might even say) on the other, and the next one for the previous two, and so forth—until such point that from the succession of pictures and their visual captions, we begin to work out the populated anxieties of each picture with the vacated anonymity of the other. Thus viewed, pictures provide the encoded messages of their own visual culture, without any undue anxiety about social, political, or cultural frames of references—which are the only sorts of registers that the aggressive anthropologization of the work of art can allow—and thus the calamitous condition of the contemporary works of art that come from the alienated boundaries of the European or American imagination: They are denied the paradoxical (and thus pregnant) dialectics of their formal abstractions informing their narrative moods. Only by allowing the totality of a lifework to work out its own aesthetic underpinning, the counter-metaphysics of its own visual rhetoric, can specific works of art show and tell the hidden anxiety of their creation.

The vital signs of an artist like Bahman Jalali will have to be detected in the flaunted subconscious of the work of art with his signature on it. Here we cannot do better than look closely at the series of work he calls "Image of Imagination." These are invariably made up of juxtaposed collages of pictures and texts, mostly of the earliest phase of Iranian photographic history during the nineteenth and early twentieth century. What these manufactured collages project are snapshots of a history that has long since mutated into memory, and Bahman Jalali here pushes them even further back into the repressed imperceptions of images at once illusory and yet compelling. These are vague (and yet how precise they are in their vagueness) pictures from the mind of a generation of Iranians that cannot completely remember and yet cannot completely forget mixed-up and miasmatic images of a bygone age that continues to haunt the dreams and nightmares of subsequent centuries. Invested in the porous punctualities of those images, the artist, Bahman Jalali, lives in the bodily memory of a people he thus claims and calls home.

The portrait of the artist at home—that is the defining moment of the totality of a lifework that allows art to register itself as the marker of a nation at peace (even when at war) with itself.

For the camera of Bahman Jalali to detect and cultivate a soul, the artist behind that camera will have to be given the space of a lifework within which art can articulate the idiomaticity of its own visual registers. Consider those pictures of Bahman Jalali in which he juxtaposes the written Persian script on deliberately distorted pictures he has archived from the earliest phases of photography in Iran. Here language has lost meaning and sublated into its visual, meaningless, effect. The result is a cumulative collage of visual abstractions that simulate memory in a pre- and post-memorial moment, when thing are and are not quite there, and yet precisely by virtue of that uncertainty command the uncanny, the unhomely, character of art as both sign and signifier. The author of this text, the auteur of these moving images, and the artist of this imagination, belongs to an entirely different genealogy of authorial agency. The subconscious of this artistry is yet to be mapped out, its subject is yet to be born—and in the birth of that artist, the totality of a lifework commands the lexicography of a visual modernity with body and soul, purposeful aesthetics and political resonance.

The Idiomaticity of the Artwork

Paramount in the collective work of Bahman Jalali is the presence of the artist-and-his-art in-the world. The worldliness of Bahman Jalali's work of art dispenses with all the undue anxieties embedded in the curatorial anxieties concerning what constitutes a work of art in the prevalent anthropology of despair that has now permanently marked the profession. Bahman Jalali's lifework, ipso facto, disallows essentialism, tokenism, representational identity politics, and above all the mendacious anthropologization of "other" people's work of art. Against the aggressive tokenization of the works of art, and their violent mutation into cultural icons, Bahman Jalali's lifework forecloses the possibility of reading any part of it without an awareness of its worldly totality, of its visual idiomaticity—of an artist working through the thick and thin of his people's history and giving them a photographic memory of who and what they are. At the age of the iconic mutation of the work of art into a provincially political provenance, which in fact paradoxically leads to a radical depoliticization of the work of art, Bahman Jalali's lifework demands (and exacts) from its viewers a moment of pause and silence to recall the momentous occasion when art announces its unreal authority over reality. The mutation of the work of art into an act of political representation paradoxically depoliticizes it, because a work of art is only political to the degree that it is worldly—when a work of art becomes iconic, anthropological, eviscerated of its worldly whereabouts it has in fact been too much politicized and thus effectively depoliticized (at the heavy price of erasing its visual idiomaticity).

What above all Bahman Jalali's lifework demonstrates is that when placed in the world that has given life and liberty to it, art is the record of the cosmopolis that has immediately occasioned it. Here we witness the centrality of the artist in the making of a cosmovision that at once embraces and is embraced by the world that it has imagined and that has allowed it to imagine it. It is only within that cosmovision that a sustained record of an artist will allow for the making of the visual idiomaticity of the world he or she has seen. The visual vocabulary of that idiomaticity is always pregnant with its own historical memories—memories that make them meaningful and trustworthy. The danger of museumization of the work of art has always been in compromising and debilitating the relevance and authority of that idiomaticity. An exhibition is a legitimate intervention in allowing the work of art to do what it does in the world outside only to the degree that allows for that idiomaticity to speak (to show and flaunt) its innate and cultivated language.

To conjugate and learn that idiomaticity, Bahman Jalali's lifework can be traced and tracked on any number of directions. One might begin, for example, with his "Baluch" pictures—the topography of sunburned passages of time and narrative on faces that speak a hidden history. Here, Bahman Jalali's camera is caring and attentive, mostly conscious and careful how close can it actually get to the emotive topography of a face without trespassing. One can then move to his "Architecture of Bushehr City"—mostly vacated sinuousness of lives echoed in the architectonic of their visual silences. In the vacated moments of these city streets echoes the lives of those who have momentarily vacated it. When we reach Bahman Jalali's "Architecture of Desert (Memari)" something visually seductive and palpably erotic is exuding from his camera. These pictures are visually solitary, the camera almost bashful of so much exposure stripped in front of its bewildered eyes. It is right here, in the midst of life ordinary and shapes and shadows rampant and evident that we need to look at some of Bahman Jalali's pictures of "War and Revolution." A bloody revolution (1977-1979) and a deadly war of uncommon cruelty with Iraq (1980-1988) mark the birth of Islamic revolution as a turning point in modern Iranian history. We must see these pictures of revolt and warfare as the continuation of the selfsame ordinariness that has preceded them for the brutality of war and the futility of the revolution to register their respective marks.

Before Bahman Jalali's photography of "War and Revolution" distracts too much from the more compelling fact of his lifework, we need to move along and look at what he calls "Image of Imagination." These are mostly the collapsed and collided images of lives forgone and foreclosed. They speak of and show worlds long since lost and abandoned, and yet still commanding the dreams and nightmares of a people, a nation by virtue of precisely the repressed facticities of these images.

From "Image of Imagination" we are better off moving to Bahman Jalali's "Akkas-khaneh Photos." These are mostly archival photos of people posing the occasion of an instant when they stood in front of a magic box to record their haphazard whereabouts for a posterity they knew not where and what it was (what it will be). If we are to go back and look at other photos of Bahman Jalali about "War and Revolution II" we better do them now, while we are still in the grip of his playful awareness of an age of innocence when photography was self-conscious of its social novelty. But before we are too much involved in Bahman Jalali's preoccupation with the political turmoil of his homeland, we need to take a look at his "Fishermen"—serene, busy, hardworking, and toiling in the black and white of a shade and shadow familiar to Bahman Jalali's photographic memory. The best way to conclude an unfolding reflection on Bahman Jalali's photographic idiomaticity is with his sustained record of "Portraits and Daily Life"—where reality takes over and life assumes its daily matter-of-factness.

Investing Soul in a Soulless Machine

From the flat-faced photograph of the first picture ever taken of Mollah Hadi Sabzevari in the middle of the nineteenth century to the emotively sculpted pictures of Bahman Jalali up to the commencement of the twentieth-first century, the history of Iranian modernity might in fact be considered as the chronicle of a prolonged project in which the photographic apparatus was indeed invested with that sense of spirituality which the aging nineteenth century philosopher thought exclusive to the human soul. The old philosopher was not too off the mark after all. When the daguerreotype apparatus was first brought to Iran in the course of Iranian encounter with colonial modernity it indeed lacked that spiritual depth that today gives Bahman Jalali's photographs their distinct character and visual idiomaticity. What has happened between that flat-faced photograph of Molla Hadi Sabzevari and these emotively sculpted photographs of Bahman Jalali is the story of a nation. A prolonged and enduring encounter with colonial modernity—that is what has happened—has mapped out the particulars of a visual terminology at home in Iranian modernity. From the battlegrounds of that fateful encounter a creative and critical consciousness has been invested behind the two perceptive eyes of a photographer like Bahman Jalali when he picks up his camera and through it looks at the changing shades and shadows of his universe. Bahman Jalali is as much an archivist of his nation's history as a prognosticator of its invested hopes for agential authority over is historical fate.

As perhaps best captured in his manipulated photography in "Image of Imagination," in Bahman Jalali's hands and through his lenses, time and narrative come together to suspend history and tell a different story. These photographs seem to be the untold story of a nation, dreams of a people yet to be interpreted—all recorded in visual silences for posterity to behold. Here words and visions collide to make for a superior sense of perception—where polyfocal facts of life are creatively sculpted and put on stage (a soul inhabiting their bodily awareness). The passage of time in these pictures is visually palpable, the occasion of the photograph marked by a deliberate silence that allows for the muted time to speak. In these pictures mules become cars, habitual gestures change in tonality and intentions, clothing items change with each frame, etc—and yet constant remains the returned gaze of people at the camera and the photographer. In that split second when the gaze of the photographed, the eye of the photographer, and the lens of the camera come together the visual idiomaticity of Bahman Jalali has recorded the story of his nation.

True to the history of the people it has photographed, he soul in Bahman Jalali's camera is not content. It is contentious. Between the fate of a post/colonial artist like Bahman Jalali as the chronicler of his people's passage through history and the immanent conclusion of European philosophers that art has ended and the artist is dead, there thus emerges the dialectic of a transaesthetics of difference, where the world in its worldliness must hope and expect the emergence of an art that still matters. Bahman Jalali's photography is the occasion for such a hope, the instance of this realization. What makes that hope possible is the vision of a mode of seeing that preempts its imaginative foreclosure. Watching a work of art from a part of the world we have never visited, let alone known or inhabited, is always predicated on an act of prior imagination. We always imagine a country, a clime, a claim on our fantasies before we stand before a work of art that

has come from that part of the world. That very act of having "come from that part of the world" is ipso facto, and always-already, an act of imaginative alienation, a Brechtian

Verfremdungseffekt that enables reading a work of art at the very same time that distorts it. With artists like Bahman Jalali, we are looking at an imaginative foregrounding in which the

Verfremdungseffekt has already taken place within the work of art, and as such it no longer makes a difference "what part of the world it has come from"—for thus energized by a visual repression that makes its reading possible, the work of art has already trespassed the boundaries of its own self-alienation. It thus preempts its anthropologization by prefiguring its own enabling repression, by flaunting its subconscious as if it was totally unaware of the power of its own repression. Thus equipped with a dose of creative repression that makes it creatively visible to any critical audience, the work of art looks back at its spectator, long before it has even been unpacked from the box in which it was shipped from "overseas," and installed on an accommodating wall, to be looked at by an unsuspecting observer. Watch very carefully! Bahman Jalali's camera is in reverse angle.

The Making of Iranian Aesthetic Modernity

Capturing the illusion of reality, as Bahman Jalali has done over the span of a lifetime, amounts, in effect, to mapping the visual subconscious of a people, made into "a people" precisely by way of such constitutions of varied takes on that very subconscious. In the eventual making of that visual subconscious, and as evident in Bahman Jalali's photographic archive, Iranians, as a people, have attained the measures of their

aesthetic modernity. The open-ended contours of this roadmap leads to the full and final recognition of the emotive sovereignty of the aesthetic act.

The complete retrospective of Bahman Jalali's work marks a crucial point in the history and recognition of Iranian

aesthetic modernity, which remains integral to the larger context of the rise of Iranian cultural modernity over the last two hundred years. The photography of Bahman Jalali reveals a cosmopolitan worldliness, a vision of reality rooted in an aesthetic awareness of the light and shadows of existence, that is irreducible to history, politics, or even culture. It has a sovereign reality onto itself. Ostad Jalali's work unveils, one shot after another, the prolonged and patient endurance, and the creative cultivation, of a visual intelligence that has long been in the making and that has been tirelessly at work to show and tell what it has seen and witnessed. Watching Bahman Jalali's work unveil over an almost half a century canvas is an historical privilege in having unmitigated access to

the visual intelligence of a nation. Capturing the visual subconscious of that nation over a lifetime of photography is both a privilege and a gift that very precious few artists can hope to claim. No reality can ever be immune to the emotive illusions of this body of work.

Whence that communally registered

visual intelligence, wherefore that cultivated vision? The only reliable guide into the sinuous labyrinth of Bahman Jalali's photographic memory of his journeys of visual discovery are his pictures. But the social conditions of their production and exhibition are also the indices of how we find ourselves standing in front of his pictures in Barcelona or Hannover. For Bahman Jalali's work not to be assimilated into yet another aesthetics of indifference, or else anthropologized into the indices of an information bulletin about the politics of his homeland, it is imperative to place it within the context of Iranian

aesthetic modernity. In order to do so, first and foremost we need to clear a false binary opposition habitually posited between a stubborn

tradition and a wayward

modernity. Mapping the visual subconscious of a people is a sustained aesthetic project, in the creative formation of which signs assume a reality

sui generis and as such remain irreducible to any false binary opposition.

Habitually, discussions about Iranian visual, cultural, or political

modernity is placed and juxtaposed against the abstract notion of a

tradition that is categorically ahistorical in its origin and provenance. A historically fixated conception of

tradition and a correspondingly alien understanding of

modernity are habitually placed next to each other by way of understanding the manner Iran was ushered into its current history, and its artists and intelligentsia into their corresponding visions of historical realities. Photography as an art form began in Iran almost simultaneously as it did in Europe; and thus it is imperative that Bahman Jalali's work be seen in the global context of this art form and never degenerated into a political index of his country of origin. There is nothing particularly Islamic or anti-Islamic about Bahman Jalali's art, nothing particularly political or apolitical. Reduction of art to political allegory is the most troubling analytical reductionism rampant in the European encounter with non-European art. This is not to deny or compromise the vast and varied social implications of his work, but in fact to meet and measure their imports in their own terms. To converse with Bahman Jalali's art we need to have a set of aesthetic sensibilities entirely alien to any falsifying reductionism and derived from the visual protocols of his work itself.

To decipher those protocols, we need to place the visual vocabulary of Bahman Jalali within the larger context of the aesthetic modernity that has actively nourished it, and then trace that aesthetic modernity to the prolonged Iranian encounter with European colonial modernity—a paradoxical process at once enabling and traumatizing. It is ultimately through the enabling force of an historical trauma that we must come close to Bahman Jalali's work. The historical fact of Iranian modernity is that it was ushered into the sinuous labyrinth of its culture through the gun barrel of European colonialism, to the point that what we are witnessing in Iran and its neighboring countries is not a copycat take on a universal conception of

modernity but in fact what can more accurately be described as the power of an "anticolonial modernity"—namely revolutionary reaction to a mode of paradoxical encounter with the master-notions of Reason and Progress when human agency and autonomy is ascribed to a people precisely at a moment when it is effectively denied them.7

Anticolonial modernity is the inaugurating moment of rebellion against that imposed and unexamined assumptions of Reason and Progress by way of a revolutionary reason that posits its own notion of progress.

This notion of

anticolonial modernity, within which specific moments such as the aesthetic modernity that informs Bahman Jalali's work occurs, points to the condition of coloniality, and by extension that of postcoloniality, that is conducive to manners of articulating a mode of agency beyond the tradition/modernity binary and as such will require a particular attention to the poetic ruptures deliberately interjected in the prose of history. The aesthetic domain in and of itself occupies a space at once autonomous and self-generative and yet coterminous with the larger political battlefields to which it is an interested witness, and precisely in the tenuous borderline of that complicitous contingency a work of art acts as catalyst of normative and moral change without being implicated in the banality of the political day-to-day-ness.

Thinking of Iranian visual modernity and the place of Bahman Jalali in it will inevitably require a conception of premodern heritage of aesthetic visuality, a historical awareness without historicism. A preliminary archeology of that premodern history of visuality unearths a long and variegated heritage, with certain solid hallmarks: The Qur'an, for example, ought to be seen not just as a juridical source of potentially banning visuality, but in fact an invitation to it: In such verses as "Those who believe in the unseen and keep up prayer and spend out of what We have given them" (II: 3), in chapters such as "Joseph" (Chapter XII), in episodes such as that of the Prophet's nocturnal journey to the heavens (Mi'raj), in the aesthetic rendition of the word of God in beautiful calligraphy, and in the melodic and rhapsodic recitation of the word of God, we see these fixation with visuality and orality perfectly evident. The belief in Mi'raj in particular has an exceedingly visual dimension to it, for it is here where the anxiety of visibility becomes very acute. God Almighty, which must remain the Supreme Unseen, so that the very notion of visuality is made possible, is here the subject of a prophetic visitation from earth. The nocturnal visit of the Prophet to meet the Almighty face to face is perhaps the most creatively traumatic moment in Islamic metaphysics, from which the very notions of visibility, and thus of visuality, are made possible.8 The centrality of God the Unseen in the Qur'anic

revelation makes the trauma of visibility central to the Islamic visual culture.

This transgressive penchant for visuality is equally evident in the masterpieces of classical Persian poetry. In the

Khamseh of Nezami Ganjavi (1141-1209) the episode of

Mi'raj becomes a central moment of reflection on visuality, visibility, and the most spectacular poetic reflection on what it means to visit the Invisible. In Ferdowsi's (935-1020)

Shahnameh too we have both a theological and a narrative awareness of the question of visuality and visibility, which in turn are written into the fabric of his poetics. Early in the

Shahnameh Ferdowsi says:

Zeh Nam-o Neshan-o goman bartar-ast,

Negarandeh-ye bar-shodeh peykarast.

Beh binandegan Afarinandeh ra

Nabini maranjan do binandeh ra—

[He is too lofty to have a name or a sign,

He is the Designer whose firmament is erected high.

You will not be able to see the Creator,

Do not uselessly bother your eyes.]

In both

Khamseh and

Shahnameh, the doctrinal invisibility of the Invisible becomes the hidden poetic eye for detailed poignancy in a deeply ocularcentric poetry.

The varied manifestations of these transgressive attractions to visuality expand and extend all over Iranian and Islamic cultural heritage. In the so-called Persian miniature paintings we are witness to exquisite manuscript illustrations that at once complete, complement, and even compete with the narrative thrust of the manuscript they are meant to illustrate. In these manuscript illustrations, the element of visuality in effect assumes a reality

sui generis, conditioning a semiotic crisis in the creative consciousness of the text, at once enabling it to exude an open-ended hermeneutics and then wedding the implicit poetics of that hermeneutics to a pronouncedly visual aesthetics. The same is true about the genre of "Coffee House Painting," a particularly popular kind of narrative illustrations that extends the domain of visibility and visuality, and with it a new set of aesthetic sensibilities, out of the courtly milieu and deep into the thicket of popular imagination, where it could roam freely. What is particularly important here is the imaginative fusion of two distinct modes of narrative, one Iranian and the other Islamic. The popular blending of the two narrative modes into a singular set of stories let loose an avalanche of visual illustrations with a distinct pleasure in making the epic of visibility at once adventurous, romantic, pious, and ritual. The fusion of the sacred and the sacrilegious, the heavenly and the mundane, in "Coffee House Paintings," now begins to push the domain of the subversive visual into the public domain.

The domain of visuality has never been limited to visual art and in a series of Persian and Arabic philosophical and mystical treatises the subversive forces of these two discourses have had a profound visual implication. Entirely tangential to his philosophical and scientific projects, Avicenna's (973-1037) "visionary recitals," as Henry Corbin rightly calls them, or "mystical treatises," as they are commonly known, point to a particularly powerful philosophical ocularcentricism that are yet to be fully grasped and understood.9 In such treatises as

The Recital of Hayy ibn Yaqzan,

The Recital of the Bird, and

The Recital of Salaman and Absal, we are witness to a particularly suggestive set of visually allegorical accounts that explore the sinuous sides of a creative imagination entirely ocularcentric in its hermeneutic energy and visual registers. The same set of factors are evident in Shihab al-Din Yahya Suhrawardi's (1155-1191) visionary recitals, treatises such as

Risalah al-Tayr,

Avaz-e Par-e Jibrai'l,

Aql-e Sorkh,

Ruzi ba Jima'at Sufian, or

Fi Halat al-Tufuliyyah, etc.10 These visionary recitals partake in a deeply ocularcentric narrative to explicate their deeply subversive modes, and thereby extend the seditious force of their narratives into visual registers.

The project of European modernity came to much of the world through the gun barrel of globalized colonialism. The direction of the gaze that the mirror of colonial modernity made possible was contrapuntal. The colonized looked back at the colonizer, as the colonizer was seeing himself in the mirror of modernity he had given to the colonial to hold and behold. The colonial person, thus designated, was yanked out of moral and normative submission, dragged out of paradisial conception of humanity as the mirror image of God, and cast onto the mirror of colonial modernity, in reverse. Colonial modernity became the most traumatic event in the paradoxical making of visual modernity—at once constituting and negating it.

Antoin Sevruguin's was the first Iranian photographer to focus on the aesthetic, as well as the documentary potential of photography. Images like his haunting portrait of a veiled woman, "Veiled Woman with Pearls" (1890-1900), brought a new sense of portraiture to turn-of-the-century Iranian photography. Meanwhile, the introduction of monofocal perspective in Iranian visual vocabulary added a new element to the hitherto polyfocal perspectives that had existed in Persian painting. This added perspective sculpted a vision of reality, of a multi dimensional humanity, distinctly evident in the aftermath of Iranian encounter with colonial modernity. Humanity at large became at once visually sculpted and morally self-referential.

This constellation of visual self-discoveries ultimately brings us to the emergence of Iranian visual modernity, to the threshold of the rise of a visual humanism that categorically brings humanity out of its Qur'anic/Biblical narrative and allows for the aesthetic creativity of the artist to mimic or modulate the divine creativity at the center of premodern experience. If

Sapere Aude ("Dare to Know") was the principle motto of the European (for the rest of the world Colonial) Enlightenment, daring to look at oneself as the object of nothing more sacred or certain than the visual apparatus of an overtly self-conscious visibility was the way in which the colonial person reasserted agency in history.

What is most visible in Iranian visual modernity is the evident traces of history on the aging contours of the fragile humanity it portrays. This is the visual equivalent of the Cartesian cogito, the aesthetic rendition of the knowing subject, given agential autonomy to perceive and conceive itself, while always already under erasure. The seeing person becomes the author of historical agency. The metaphysical certainty of the world loses its magical illusions right in the enchantment of an evident reality that is auto-narrated. In the vistas of this visual modernity, humanity becomes evidently fragile, at once vulnerable and venerable. This is both a restitution of the sacred and the simultaneous celebration of the profane, the ordinary, the perishable. There is an almost palpable Khayyamesque vulnerability about this vision of humanity, hanging on an existential angst that may or may not be the signs of the time it registers. From the poetry of Nima Yushij to the fiction of Sadeq Hedayat are the existential foregrounding of this renewed, surreal, conception of humanity.

What we are witnessing and celebrating in Iranian visual modernity, with Bahman Jalali as its

locus classicus, is the commencement of an aesthetic humanism (at once authorizing and transitory) otherwise unprecedented in its long and varied history. What holds together and balances this aesthetic humanism is no fabricated binary between a fictive tradition and an elusive modernity. The thrust of this humanism ranges from the deepest thicket of a people's collective consciousness down to the creative effervescences of artists like Bahman Jalali who are at one and the same time of a particular cultural location and yet belong to a cosmopolitan worldliness at home anywhere on this small and vulnerable planet.

“Desert Architecture series” Bahman Jalali: All rigths reserved © Rana Javadi

“Desert Architecture series” Bahman Jalali: All rigths reserved © Rana Javadi