This interview was recorded at the artist's studio in New York in July 2014, in preparation for the exhibition Shirin Neshat: Afterwards, 9 November 2014 - 15 February 2015, at Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha

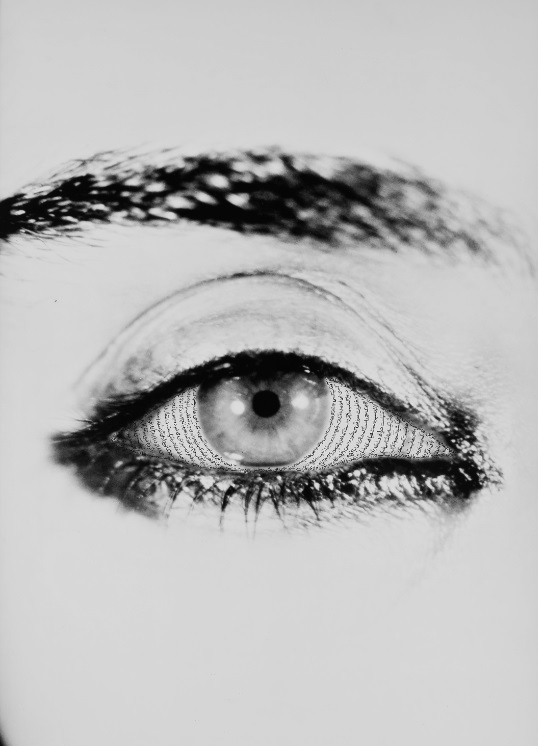

Shirin Neshat, Offered Eyes, 1993, ink of RC Paper, 133cm x 92.1 cm.

Shirin Neshat, Offered Eyes, 1993, ink of RC Paper, 133cm x 92.1 cm. Copyright Shirin Neshat. Courtesy Gladstone Gallery. Photo Plauto

Abdellah Karroum (AK): Shirin, yesterday we were here talking about a title for the exhibition and so today, to help people to understand the work. I wanted to start with a very basic question about the inspiration, the readings, the history from which your work comes, about its origin. Because if we start at the end and look back at your work, we see the presence of women, the figure of women, the body of women; they have had a constitutive presence since your earliest works. It's continuous: there are the histories and the ideas, but there is also the presence of the female body as maybe the most important creation. When I look at your work, I understand that the inspiration derives from both outside and inside of this body, from this tension between inside and outside. Can you explain, in your words, where your strong expressions and creations come from?

Shirin Neshat (SN): Like many artists, it is at times difficult for me even to understand my own tendencies and recurrent obsessions. For example, why did I become an artist in the first place? Why am I drawn to certain subjects and aesthetics? But now, after so many years, I'm able to look at my own work retrospectively and analyze the roots of my ideas and visual vocabulary.

Among things, I have discovered that I tend to repeat certain patterns. For example, as you mentioned, the human body, particularly the female body, has become a central theme in my work. Perhaps this is partially due to the fact that I am myself a woman, and partially because the female body has been perpetually such a controversial and problematic subject in my Islamic background. I see the use of poetic, allegorical language as the key entry point into my work, revealing the influences of my Iranian cultural background, a country rich with its history of poets and mystics. I see how the development of my personal history has been integral with the development of my art, informing and defining my forms and content, making my work personal if not autobiographical.

And finally, I have detected how my work addresses the Iranian identity crisis, that perpetual conflict between their Persian versus Muslim heritage. Aesthetically, the sense of symmetry, harmony, repetition, void, abstraction, and integration of text with image borrows from Classic Islamic art, while the notion of mysticism, poetry, and the narrative structure seems to stem from the traditional Persian background, Persian miniature paintings, in addition to Islamic art.

AK: You were talking about looking and reading, and so I wanted to ask you about the relationship between art and history and what art does to history?

SN: I think artists have a way of interpreting history that is quite different from any historian or academic, possibly because their approach is so often non-factual and indirect. In my case, it's been my own recent discovery that through my work, whether photographic or film based, I have also been capturing moments of history. The Women of Allah series, for example, was a direct response to the 1979 Islamic revolution, my feature film Women Without Men captured Iran in 1953, while my recent series The Book of Kings relayed my personal response to the Green Movement in Iran (2009) and the popular uprisings throughout the Middle East, namely the Arab Spring in 2011.

Stories of Martyrdom, from the series "Women of Allah", 1994. Ink on silver gelatin print, 38 x 51 cm.Collection of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha.

This being said, I feel that while my art metaphorically documents political history, it remains non-ideological; it frames questions without ever providing answers. This same approach applies to my curiosities about Muslim women. I've tried to never be judgmental, and have simply attempted to comprehend the emotional and psychological states of women who live under extreme religious environments.

AK: Yes, but at the same time, history and the female body are at the center of your work and the point of departure comes from you, your feelings.

SN: Absolutely.

AK: I think this is why I see the female body as the center, as the object itself. But it's not only the object. It's the model you use as a reference, a stage, for action.

SN: I have always found it fascinating how in Islamic cultures, the female body has been a battleground for ideological and religious values, and how in many ways Muslim women embody men's rules. Therefore, in the Women of Allah series (1993–97), I was not only interested in the notion of feminism, but also felt that through a study of women during the Islamic Revolution, I could approach an understanding of the philosophical and ideological basis behind the revolution itself.

Looking back at Iran's modern history, it is astonishing to find how each time there has been a political transformation, Iranian women's private and public lives have been transformed too. For example, during the Reza Shah Pahlavi's regime (1925– 41), women were forced to unveil, then after the Islamic Revolution (1979), they had to mandatorily veil themselves.

Interestingly, a close examination of the Women of Allah images (1993–97), made about the Islamic Revolution, and The Book of Kings series (2012–14), documenting a more recent Iranian history, reveals a major shift in Iranian society and the condition of women within the span of thirty years. If the earlier series shows how religion dominated women's private and public lives, the later series reveals a new generation of women, who are educated, modern and vocal, and most importantly consider religion as a choice.

AK: Is your approach then a cultural reading about Iran and the Iranian women?

SN: Yes and no. You must keep in mind that my work is highly stylized, possibly due to the fact that I don't live in Iran, and therefore my art has never been about capturing the "truth," rather it's a fictional approach to the "truth." And consequently, while on the surface my work appears ethnicity-specific, it tends to transcend the questions of time and place and have a more universal resonance, appealing to those from other ethnicities and religions.

Having said that, while my perspective is that of an outsider, of an Iranian artist living abroad, I have given myself license to indulge in raising questions about my own culture's past and present history, even if from a distant point of view.

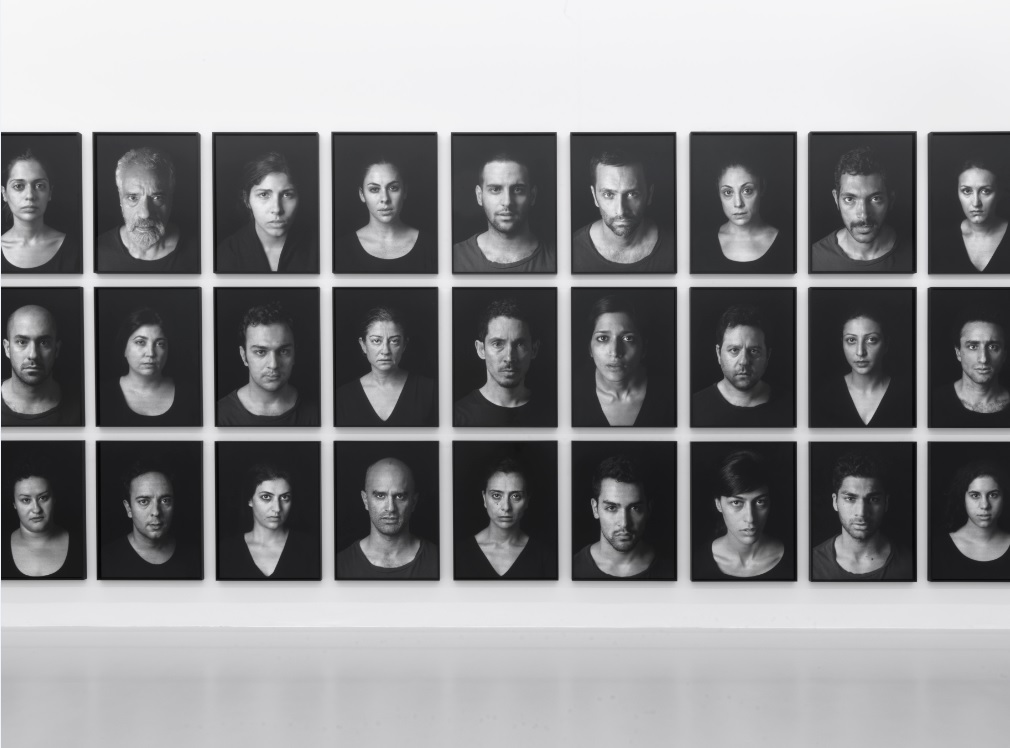

And finally, my images from both the Women of Allah (1993–97) and The Book of Kings (2012–14) series are portraits that are not attempting to capture each character's personal identity, but rather are meant to offer a glimpse into a collective identity, a means of portraying some moments in our national history. In the case of The Book of Kings series, I consider them one narrative, as one large photo installation. So oddly enough for the first time in my photographic work, I find myself in the position of a storyteller even through my photography.

AK: A witness.

SN: Yes, like a witness, who is always observing things from a distance and speaks to her viewers with an emotional not a political tone. I guess I am interested in history not so much as a way to document political events but as a way to study the power of human spirit in light of struggle and survival in times of tyranny.

AK: But it's not The Second of May (1814), it's not Goya. It's not the one specific moment of the drama, of the history; it's beyond that. It's trying to talk about the masses, for example, or about the effect of making conventional decisions, like values that are imposed on the population as part of history or as instruments of power.

SN: Yes I agree, and in the case of Goya's painting The Second of May, I believe it is the emotional force behind the scene that moves us beyond belief as opposed to the specifics of his subject matter. Maybe the best political art is the one that can transcend time, place, and even politics itself.

AK: To return to this relationship to history, to what art does to history, I also wanted to ask what art does to mythology. Because to create an image within the universe of art, you look to history that you respond to, communicate with, and try to understand. And now mythology has become really important, especially with The Book of Kings. So what does your work do with this mythology and with questions of witnessing versus reading, connecting or rewriting?

SN: I remember the series began right after the inspirational Green Movement (2009), a popular uprising in Iran, which was horrifically suppressed by the Iranian government. I had been somewhat involved in supporting the movement, and I remember how devastated I was by its aftermath, witnessing a magnificent and euphoric Green Movement turn so tragic and violent. Right after that experience, I felt an urge to create a series which captured the spirit of patriotism that had become so powerful and contagious amongst the youth, and that consequently moved so many of us.

But knowing that I needed to find a more mythical way of expressing my impressions and ideas, I began by looking at the original The Book of Kings (c. 930 bc), Shahnameh, which is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi in the 10th century. A monument of poetry and historiography, Shahnameh mainly tells the mythical and to some extent the historical past of Iran, from the creation of the world up until the Islamic conquest of Persia in the 7th century.

I found that the core themes in Shahnameh were similar to what I was trying to express. How the notions of patriotism, devotion, and sacrifice repeatedly intersect violence, atrocity and ultimately death. Ferdowsi documented ancient Persian history through the language of poetry and mythology, and I too was revisiting the notion of "patriotism" in the present time through my visual and allegorical language. I saw a definitive connection between my country's past and present, between Ferdowsi's mythological narratives and characters and my own way of organizing ideas about our present day's heroes and villains.

The Book of Kings series, 2012. Ink on LE silver gelatin print, 152.5 x 114 cm.

AK: So your work brings this reading of mythology and the interpretationb of history to understanding the present.

SN: Of course I never rationalized it as such while I was creating this series, but I do think my approach has been a poetic, mythological interpretation of history, not a realistic one. Each one of my characters from the "Patriots," the "Masses," and the "Villains" embodies a certain type of myth or parable.

AK: Because with history, we don't always know what is real and what is fictional, what has actually happened and what are constructed narratives.

SN: That's very true. And perhaps the narrator should, at the most, present the story in a way that allows viewers to determine the "truth" themselves. I remember during the planning of my first feature film, Women Without Men (2009)—a film that takes place during the summer of 1953, when a coup organized by the American CIA toppled the Iranian government and removed the Prime Minister by force—I was shocked by how different parties interpreted history differently. When speaking with pro-Shah supporters for example, they denied a coup ever actually took place and believed it was a complete fabrication. When interviewing ex-communists, they claimed that the coup was a strategy to eradicate communism from Iran. And finally, from the historians' perspective, the coup was a proven fact to the point that even the American government had admitted and apologized for this conspiracy. So at the end, the film approached political history only on an allegorical level, never with certainty or realism of any form.

AK: So this distance of you being in exile, it's not something necessarily taking you out, but also up. It's an exile that can be seen as a kind of elevation, where you have a wide picture and you see from far away and, for example, you see the masses. You start the Afterwards exhibition with the masses and you see different groups of people and it's like extracting yourself. Not extracting but…

SN: This is very true, I have always seen myself standing in the background and observing history unravel. Although I must admit this was not the case in Egypt; I did experience Cairo in its revolutionary days in Tahrir Square (2011–13), and I did interview and photograph many elderly Egyptians.

Masses, from The Book of Kings series, 2012. Ink on LE silver gelatin print 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Installation view from the exhibition Shirin Neshat: Afterwards, 9 November 2014 - 15 February 2015 , a t Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha

Masses, from The Book of Kings series, 2012. Ink on LE silver gelatin print 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Installation view from the exhibition Shirin Neshat: Afterwards, 9 November 2014 - 15 February 2015 , a t Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art, Doha

AK: Do you want to recreate these different entities in ways that preserve this tension? Looking at the work in the exhibition, we look at the "Masses," the "Patriots," the "Villains." You put different works in succession so that one work looks to another work. Or you put people, the audience, in front of one work and then the other, to show different possibilities. And then there is the relationship of attraction or resistance.

SN: I would say it's more about the relationship between fear and the resistance against fear. When I started the project, I knew the photographs had to be divided into three groups: the "Villains" who hold power, the "Patriots" who fight power, and the "Masses" who are the bystanders, the witnesses to this tension. But unlike the Women of Allah series, in which each image independently contains its own concept and narrative, with The Book of Kings, I found that the images had to work in relationship to each other, and that the viewer had to be surrounded by all three entities in order to sense the tension. So at the end, the series became one large photo installation composed of sixty-five photographs. Very similar to the Women of Allah, The Book of Kings remains visually and aesthetically minimal, black and white, graphic, with subtle human gestures. If the body language of the "Villains" suggests the notion of power and dominance, the "Patriots," with their hands on their hearts, suggest the notions of love, devotion, pride and defiance, while the gazes of the "Masses," on the other hand, reveal a sense of vulnerability and fear of loss and mortality.

AK: And in your video installations, Turbulent (2018) or OverRuled (1998), for example, it is also more than a story, because by putting the viewer behind the screen, you put people in a situation where they become part of this empty space and these voices.

SN: I find there is something magical about the moving picture that helps transcend the limitations of still photography. With video installations one can incorporate a dramatic development, landscape, choreography, language, and music. Also, the video installations offer the viewer more a physical, rather than a sculptural, experience that is absolutely lacking in photographs. In the case of Turbulent, which is a double-channel projection on two opposing walls, the audience member is seated in between the two screens and becomes an active participant, caught in the midst of a musical duet, in between the male and female singers.

In OverRuled (2011), which is set as a fictional and absurd courtroom scene, the audience is confronted with a different form of opposites. A judge and his peers, representing men of the power, authority, and rhetoric, sit on one side of a table, while two musicians, whose crime is the subversive nature of their songs—ironically, poetry written by the 13th-century poet Rumi—sit on the other side. If Turbulent (1998) addresses the question of masculinity and femininity within Iranian society, OverRuled, highly stylized and surrealistic, captures the disparity between those who hold power but lack imagination, and those who have imagination but lack power.

AK: Turbulent is really about the tension between presence and absence. It's very strong.

SN: Turbulent is truly a work that functions on both conceptual and sociological levels. The absence of an audience for the female singer could be interpreted as a symbolic representation of how women are deprived from the experience of singing in Iranian culture, yet it can also be seen as an opportunity for the singer to express her inner freedom and creativity. The presence of the audience for the male singer is equally both an endorsement and a handicap.

AK: Does your work have an autobiographical aspect?

SN: I would say that my work is certainly inspired by my personal life circumstances and the existential issues, but it is not necessarily autobiographical. When I look back at my art, I see how, for example, every female character embodies aspects of my character and mirrors my own weaknesses, vulnerabilities yet strength, hopes and aspirations.

Also, looking back at my own pattern of narratives and concepts, I see how the notion of "exile," for example, has been a recurring theme, a subject very close to my experience. In the video installation Tooba (2002), a frantic crowd of men and women dressed in black runs to take refuge in a garden with a single tree at its center.Here the garden and the tree of Tooba, which originates in the Qur'an, symbolizing the sacred tree in paradise, become the allegory for exile. The narrative of Women Without Men, on the other hand, evolves around an ephemeral, mysterious space of an orchard, which also gives the few women characters shelter, so they may recover from their emotional, psychological, and cultural wounds.

AK: What about the creative process? Is it something you can feel or name? Is there something that you are conscious of as the reserve of your creativity?

SN: The creative process has been the saving grace in my life. It has given me a sense of purpose and meaning. It has helped me find ways to express everything that I cannot express in words. Also being an artist has made me feel responsible to the society I live in and to the society I come from. Through my art, I feel constantly engaged with the public, with various audiences and communities.

Also, I should mention that ever since I became a professional artist, there has been no separation between my personal and professional life. I have immersed myself in my work to the degree that is reflected in my lifestyle. To support my own obsessions and to remain stimulated, I have surrounded myself with other artists and collaborators, who constantly engage me into cultural, political, and intellectual dialogues.

AK: It is what brings light as well.

SN: It's very grounding.

AK: At the same time, though, it's dark but it brings awareness.

SN: I guess my view is that art should disturb, it should capture both the dark and the bright sides of our humanity. There is something honest and moving about being confronted by both the horror and grief, yet the beauty and pleasure that exist in the life we live in.

AK: That's fantastic. Now let's go back to the basic, simple questions. You talked about the book so, tell me, what were your first readings?

SN: While I'm not a big reader, I would say that literature has played a big role in my work. I have mainly gravitated toward Iranian female poets and writers. I am somehow emotionally connected to the way these women have expressed their personal and social crisis.

So I very often approach literature as the subtext of my work. As you know, in 2009, I adapted the well-known magical realist novel Women Without Men, by the Iranian writer Shahrnush Parsipur, into my first feature-length film. Also, the calligraphy inscribed on my work is poetry that has become integral to the meanings of my images. And at times, my images are created in response to a particular poem that I have read and have been inspired by.

Among the poets, I have particularly admired and have been inspired by the work of Forough Farrokhzad, who unfortunately died at a young age in a tragic accident in the early 1960s, but left a tremendous legacy behind. I have always felt an affinity with her emotional and feminine expression, with her subversive language, and in the way that she so fearlessly tackled the sexual, social, and cultural issues of her time. In general, I have seen the role of text in my images as a form of "voice." The poems give an emotional and intellectual strength to the faces, which on the surface appear silent and expressionless.

AK: So it departs from the real image, the presence, from something that is immediate and confrontational, and that goes to the past.

SN: Exactly. And of course very often, particularly with my video work, I use poetry by Rumi and Hafez. I really appreciate the juxtaposition between ancient literature and contemporary social reality. In many ways the songs in my videos replace the calligraphy inscribed on my photographs.

AK: I think that what we can read is that these multiple layers are also multidimensional. If you have one image, one form, you have also something that is not complete that you want to complete. You use different languages to make it the most complete.

SN: Exactly. The text and the image together.

AK: Last question. How did you start working? What do you consider as first, as foundational?

SN: Of course as a young child I always had a romantic idea of becoming an artist. But this romanticism quickly vanished when I began my studies at art school in the United States and came to the realization that making meaningful and relevant art is very challenging; ideas don't just grow intuitively. I felt that I lacked the maturity and the experiences that were necessary in order to make significant art. So eventually, after I graduated from art school and detected the mediocrity of my own art, I decided to move to New York and abandon art altogether.

My eventual return to art twelve years later was certainly not due to a career strategy, but because of the overwhelming sense of nostalgia I felt ever since my separation from my family and country. Visual art became the only language that I could feel comfortable with, in order to explore and express both my questions and my findings. Today I understand how my early years in America, the tremendous sense of nostalgia, and anxiety are imbued in all of my narratives and characters. So again what I find fundamental to my development as an artist are my personal circumstances and the emotional state of being caught between two cultures in conflict, not only in politics, but also in values.